The Messy Path to Happy Destiny

- 8 October 2020

- BySarjé Haynes

Big Cartel Art Works is our initiative to provide work, opportunity, and creative freedom to artists in this time of uncertainty. As the pandemic has intersected with overdue discussions on racism and inequality, we'll be commissioning some projects that stretch beyond our normal areas of expertise. Right now, it's time to learn and elevate stories that we all need to hear.

We're doing our work to understand - and undo - the harm caused by systemic racism and racist atrocities. Today, painter and writer Sarjé Haynes shares her perspective of the worsening climate crisis in a series of vignettes, including what's currently happening in Oregon. Living on Chelamela, Kalapuya, and Siuslaw ancestral lands, she is raising two amazing adventure cats with her partner, in their converted school bus. You can learn more about her and buy her work at her website.

September 17, 2020: Eugene, OR

The rain hammers overhead. I hold my breath, picturing a worst-case scenario as I peer at the emergency escape hatch over our bed. If the seals fail, we could be flooded. This is our first big rainfall in the bus. It's a doozy - over an inch falls within a few hours. I'm afraid of what could happen, but what's new?

The past week has been full of foreboding. Our skies are saturated in smoke particulates from nearby forest fires. 2020 is Oregon's worst fire season on record: over a million acres have burned, and half a million people have been at risk for evacuation. Our air quality has been the worst in the world.

The same view as the smoke worsens in the Willamette Valley, 2020.

I am new to the Willamette Valley. This long, central valley stretches across the northwestern region of the state. It's home to the cities of Portland, Salem, Corvallis, and Eugene, among others. I've been an Oregonian for three years, having grown up a "flatlander."

My life has been punctuated by relocations; many as response to changes in the local climate and culture. While listening to the rain beating the steel roof overhead, I pray that I'll be able to put down deeper roots in this place.

Danger is inescapable - but this is where I want to be.

Under a bus-colored sky: the first full-day of smoke turns the sun red, and the nearby wetlands ashen.

July 1993: Chapman, KS

As my second-grade year ends, my usual joy at embarking on summer is dampened, like everything else, after weeks of rain. I trudge home to the basement apartment. Mom and I have been trying to prepare for a flood. We box up our possessions, elevating them on folding tray-tables or other flat surfaces we can find above floor-level.

One afternoon, the concrete floor begins to weep. Soon, I'm sitting in an inch, then two inches of water. When Mom walks in from work, she springs into action, calling the landlord. He arrives with his family and a Shop-Vac in tow. We move in unison, loading up his truck. They store our boxes safely, up on Indian Hill. One of Mom's coworkers kindly opens her home to us.

I receive two gentle lessons in the month that follows: I may need to know how to let things go. And, having a community who will help means we might yet survive.

The "Great Flood of 1993" sweeps across almost all the Midwestern states, and creates $15 billion of damage in the process. At the time, it seems like a fluke of weather.

May 30, 1998: Kansas to Minnesota

After several more years in our small town, Mom seeks a new career. Her opportunity arrives - in Eagan, Minnesota.

We drive nearly 600 miles. Her friend and coworker is living in the suburb of South St Paul. But this afternoon, no one greets us at the door. We head to Eagan, and stay the night in a Hampton Inn near the new job.

That night, a huge storm tears through the Twin Cities. Winds exceed 80 miles per hour. The next day, I witness downed trees all over South St Paul. Street signs are felled, vehicles damaged, and power is completely out for large swaths of the metro area (over half a million customers, we later learn). Our friends are home. Together, we muse at how our vehicle has been saved: in the spot where we parked the previous day is now a large tree limb. We are grateful that we have avoided injury, yet again.

"The Southern Great Lakes Derecho of 1998" caused tens of millions of dollars in damage. (Note: another derecho hit the Midwest in August 2020.)

In my twenty Minnesotan years, I experience dramatic changes to the climate. Several years we have "green winters” - snowfall totals dip from the routinely-average several feet, to only several inches. Temperatures become more extreme: higher-highs in the summer, lower-lows in winter. Sometimes we have weeks of what feels like lung-collapsing cold.

I don't know what it means. My high school curriculum suggests these changes exemplify "Global Warming."

Adults who aren't teachers tell me that's probably not true: "These things happen, cyclically. We're just in a warming cycle. Don't worry about it."

So, I try not to worry about it.

2006: Miami and Mississippi

I'm in my sophomore year of college. Depression is circling over my head like a vulture. I leap at a chance to travel, to escape my own thoughts for awhile. I take two bus trips.

The first is to Miami to perform with the university's jazz band. I spend January vacillating between miserable and manic, consuming as much alcohol as I can. I can’t understand this place. It seems to have no apparent middle class. I count dozens of luxury vehicles, passing beggars in the street. I feel lost. I drink even more, and spend the return trip dead to the world, unable to be awakened as I "sleep off" alcohol poisoning.

March brings Spring Break. The second trip is to Waveland, Mississippi. In advance, we're warned: no alcohol, no cigarettes, no drugs. This is a service trip, not a vacation.

I need this.

I find myself emotionally overwhelmed by the contrast to South Beach. We’ve chosen to come to a coastal community that was nearly flattened by Hurricane Katrina. We sleep in a tent city. The area is barren and creepy. My peers and I marvel at spray-painted plywood signs across the landscape. Messages that read: "Don't forget about us," and "State Farm Sucks!" We sneer at the rare property that has been restored. An intact home, complete with landscaping, looks deeply out-of-place, here.

We spend a day cleaning up a beach. I find myself repeatedly stopping to look at the massive pylons standing in the water: concrete structures which are all that remain of the destroyed I-90 bridge, across the Bay St Louis.

One day is spent gutting a woman's trailer: removing anything we can to eventually be collected by the Army Corps of Engineers. The response time in Mississippi has been dreadfully slow under George W. Bush's administration. The woman tells us she's so grateful to have our help. "Don't worry about saving anything," she says. "I've let it all go."

But we find a cache of photographs that have withstood the storm, and several other trinkets intact, which we salvage into two banker's boxes. The woman cries at our compassion. "I didn't think I'd see any of this again. My kids made these!"

For the first time in my memory, I feel a sense of purpose. Perhaps even a twinge of faith. It feels right to be helping people. It feels right to show others that I care.

May 22, 2011: Minneapolis, MN

I'm living with my chosen family, my best friend and her dad. After trying to find meaningful work, then any work, I’m killing time in suspended animation thanks to the Great Recession.

A storm pushes through the North Side. It just seems like a typical thunderstorm to us, but we soon discover that a tornado has hit our urban neighborhood. Just a few blocks away, the edge of the storm has destroyed homes. Miles of this community are damaged. The damage festers, like an open wound. I realize, much later, that environmental injustice is markedly worse in urban areas, because the United States is a racist place. We are racists in America.

We wait for meaningful change, but no one with the power to do it arrives.

Within another few years, I begin to work for a discount grocery store in North. Finally, I get to be useful! Living in a "food desert," this feels like worthy service, providing nourishment to my community. I’m earning a good wage. I step into a leadership role. Life is improving.

I meet Chris online, and after a lengthy phone call, we have an early-morning date in downtown. We talk about someday living in the Pacific Northwest.

December 2015

After having a near-death encounter with a car, stumbling home from a bar on a weeknight, I’m laid up with a horrible sprained ankle. I’m using any excuse to drink again. I feel lonely and hurt by life, despite all the good that’s in it. I’m hurting myself more frequently, and I know this is hurting my family, too.

Several weeks of drunken soul-searching pass, before a moment of clarity arrives: all that I love will be lost, if I cannot quit this addiction. As I weep alone in my bed, I give up my resistance to that word: alcoholic. It suits me, after all.

The next day, I am greeted warmly by women who practice sobriety. I learn about the concepts of Unity, Service, and Recovery. I finally, truly feel at home.

2020: Oregon

We’ve moved to a small, conservative community in southern Oregon. After three years, I grow weary of witnessing hostility to outsiders. In particular, locals disparage the homeless. I wonder how this community will handle increasing numbers of "climate refugees” - those who must relocate because of extreme weather events.

As the pandemic rears its ugly head, we decide to do something different. Chris and I buy a school bus, and begin the process of converting it into our new home.

“We bought a bus!” Driving home through the eastern high desert of Oregon.

We move from a three-bedroom rental into less than 200 square feet. With time and effort, we find our way into an intentional community. We are now learning to grow food for our own subsistence - including raising and humanely butchering meat animals. We study the important skill of Liberation Listening, a method focused on unburdening ourselves from the systems of oppression that still rule our society.

A week into our new life on this farm, the smoke rolls in. The community pulls together. We discuss how to prepare: stockpiling water, removing flammable materials. We contemplate what we'll do if fire gets closer. It's unnerving, but I'm feeling indescribably grateful as we honestly assess the way forward. This is a stark contrast from much of modern discourse: combinations of small talk and disagreement, leading nowhere.

Our community works together, preparing. We help each other through the emotional labor of fire: anxiety, fear, sadness - signs of grief. We also confront the physical aspect: exhaustion, sneezing, sore throats - scary symptoms in the time of COVID-19.

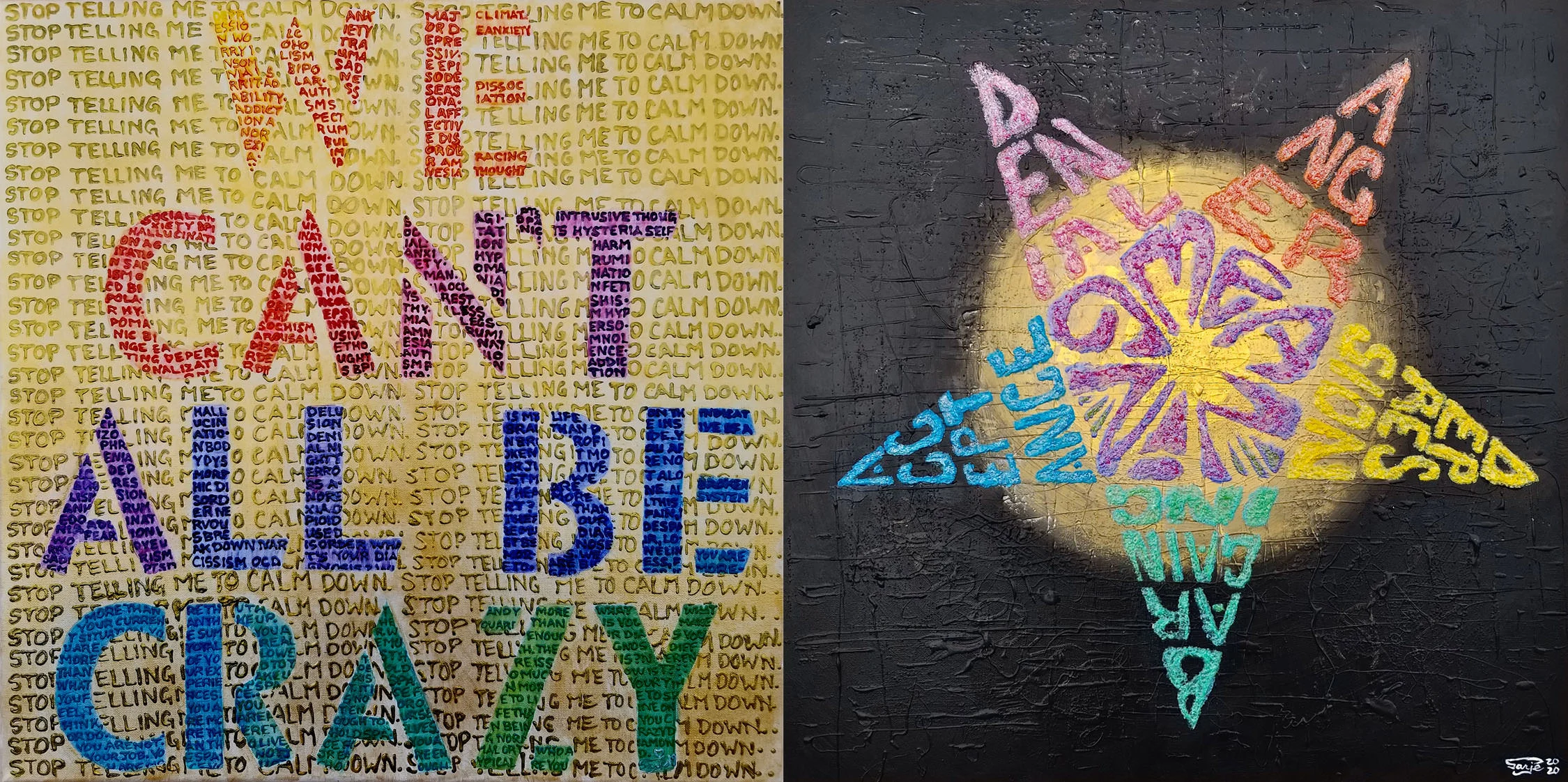

Two of my original paintings from 2019 and 2020. “Calm Down,” and “Grief is a Portal: The Way Out is Through.” You can see more of my art in my Big Cartel shop.

Just over a week later, the rains come - and the bus holds up! The ground, already saturated from our efforts to avoid fire, becomes muddy. Children run outside, playing in puddles. I walk on the path to the garden - a slogging, wet journey. We have a lot of work to do. I don’t mind.

Now is the time for us all to do our part of this work. We must confront the greatest existential threat in the history of life on Planet Earth. There’s no more time to compare notes on how much we believe that the Climate Crisis is happening. It is happening.

Our cultural collapse, spurred by global pandemic, indicates the root source of our suffering - systemic oppression and injustice at the hands of wealth; white, patriarchal, greedy hands overflowing with the rewards reaped as We The People starve.

It doesn't have to be like this.

I reflect with immense gratitude on all who have shown up to Unify in Service, to help me Recover - whether from the storm of addiction or the storms of the changing climate. Because it seems to me that life is a series of steps on a messy path, in the aftermath of storms. We can walk forward together. Our communities can recover, if we each act in solidarity and in service to one another.

This road we're trudging might lead to "Happy Destiny" yet. I hope you’ll join me. Don’t mind the mud.

“We shall be with you in the Fellowship of the Spirit, and you will surely meet some of us as you trudge the Road of Happy Destiny. May God bless you and keep you - until then.”

8 October 2020

Words by:Sarjé Haynes

Tags

- Share